Nuccio, McCrory deaths anger Manchac mob

On Tuesday, December 8, 1936, headlines in The New Orleans States newspaper read, “Opinions conflict on missing fishermen” and “Accidentally drowned, says sheriff; Foul play, kin declare.”

In the Shreveport Journal, the headlines over an Associated Press article read, “Fishermen missing for week; Believed slain, bodies hidden.”

One day earlier, according to The Hammond Vindicator, when a three-day search yielded no bodies, 36 exhausted volunteers and family members became an angry mob in response to a statement from Livingston Parish Sheriff Rudolph P. “Rudy” Easterly.

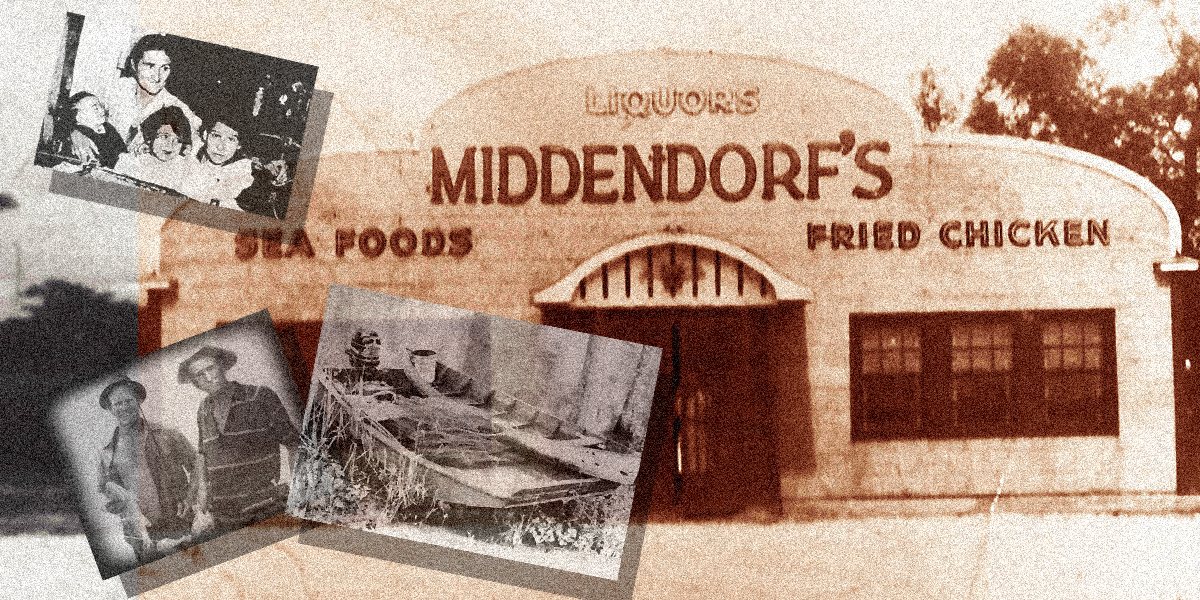

Following a late lunch with the group, the sheriff spoke to reporters while the searchers listened. The disruption started when, standing outside Middendorf’s café, Sheriff Rudy told the group that Joseph Nuccio, 36, and Nick McCrory, 32, had accidentally drowned.

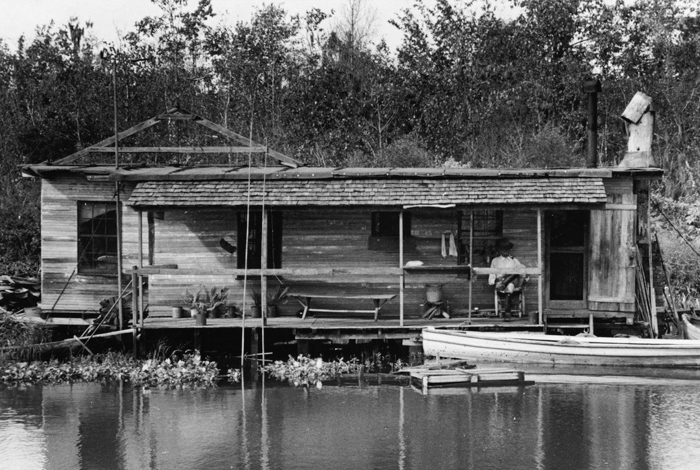

Joe and Nick left Manchac the week before, bound for their fishing camp near the mouth of the Amite River. When they failed to return at week’s end, friends organized a search party. The searchers found Joe and Nick’s water-logged motorboat securely moored in front of their fishing shack. Inside the craft, they found rusted guns and water-soaked provisions.

On the dock, the party found a dented and greasy bailing can, smudged with fingerprints, some too small to be Nick’s or Joe’s prints. The finding prompted searchers to wonder if a third party, perhaps a woman, had joined the men after they left Manchac.

The search party also discovered a small red skiff, towed initially by the two men for setting trot-lines, damaged and capsized, pulled ashore four miles upriver from Joe and Nick’s camp, surrounded by the muddy prints of bare feet.

Family members found no evidence the two men had entered their camp that morning and theorized that someone had attacked the two men as they docked at sunrise.

At Middendorf’s that Monday afternoon, Sheriff Rudy tried to calm the angry mob he created. Waving his hands, he insisted he had not closed the case and had just stated his opinion.

“And that opinion is wrong,” shouted Maurice McCrory, Nick’s brother. “The water in front of the camp isn’t even waist-deep,” he said, “And both Joe and my brother were good swimmers.”

Earlier that day, 50 men in 25 boats searched for the missing men or assisted the state conservation office, which launched a specialty rig and drug the waterway along the western shore of Lake Maurepas.

The exhaustive search had yielded only a single raincoat, tangled in fishing line at the mouth of the Amite River, near the location of the battered red skiff.

“I believe,” the sheriff said, “that the skiff overturned, sending one or both of the men into the water. Or one of them may have fallen overboard while setting lines, and the other went to his rescue.”

“At the mouth of the river,” the sheriff continued, “the water is 10 to 12 feet deep. With the lake rough and the water that cold, I don’t see how they could have gotten out alive.”

Maurice McCrory asked Sheriff Rudy if he had located the 60 crab pots his family reported missing from the camp. Maurice and his brothers had helped Nick and Joe retrieve and store the traps for winter two weeks before the men vanished.

Dennis Rottman, the search leader and Nick McCrory’s uncle-in-law, asked the sheriff how the skiff landed ashore and who made the muddy footprints.

Searcher Paul Tregre asked why the men left their provisions out in the weather and whose prints were on the bailing can.

However, the sheriff offered no answers, saying only that he was still investigating.

Concerned about Sheriff Rudy’s assessment, Ponchatoula Alderman Fred Blasdell reached out to the Tangipahoa Parish Sheriff’s Office for help.

By Tuesday afternoon, Tangipahoa Parish Sheriff Frank M. Edwards told reporters that Deputy Sheriff J. George McWilliams had resolved part of the mystery.

As State Conservation Officer Dan Lavigne worked his rig, dragging the lake for bodies, two teenagers stopped him. They reported finding the red skiff adrift the week before and pulling the boat ashore. Lavigne shared the information with Deputy McWilliams, who interviewed both brothers.

Gibson and Harry Simoneaux told the deputy how they discovered the skiff less than two miles from Nick and Joe’s fishing shack. They pulled it aground near their own camp, thinking anyone looking for it would see it in passing.

With that mystery solved, Officer Lavigne returned to the area the next day with explosive equipment on his boat in place of the dragging apparatus. Over the next two days, his craft followed the western shore of Lake Maurepas. Between the mouths of the Amite and Blind rivers, his team exploded more than 100 pounds of dynamite in under 48 hours.

Lavigne hoped to dislodge any bodies stuck on the bottom of the lake.

The operation uncovered no bodies, but Officer Lavigne, assisted by 50 volunteers, did bring more fishing line to the surface, along with a bait bucket and a ripped fishing cap, both identified by Maurice McCrory as belonging to his brother.

Hearing of these findings, Sheriff Rudy contacted The Denham Springs News. “I’m convinced now that the men drowned accidentally, probably in a squall,” he said, “I’m certain there was no foul play.”

Thursday morning, December 10, 1936, the body of Nick McCrory washed ashore on the west side of Lake Maurepas. The search party that found him included his three brothers, Maurice, Huey, and William McCrory. Millard McCrory, a cousin, and four others, Leslie Hebert, C. B. Joiner, George Clark, and Milton Baham, accompanied the brothers.

The following afternoon, 250 yards downstream and 100 yards offshore, Louis LeBlanc and Dennis Rottman found Joseph Nuccio’s body, lodged in a cypress knee, with only a portion of his scalp visible above water.

Both days, Dennis Rottman placed a friend’s body in his lake skiff and traveled to Clio on the Amite River. There, Sheriff Rudy Easterly, and the Livingston Parish Coroner, Dr. Montgomery Williams, examined the remains.

According to Rottman, the coroner described both bodies as being “in a state of decomposition, showing no marks of violence.” The coroner told Rottman that “accidental drowning” was now the official cause of death for both men.

However, Clarence Williams, who helped dislodge Joseph Nuccio’s body from the cypress knee, told The New Orleans States many still suspected foul play.

“Joe had a deep gash in his back that looked like a knife wound,” he said. “The coroner could have said the cypress knee caused that, but he didn’t. He said there were no marks on the body, and that just wasn’t true.”

“Sheriff Easterly said they would test the prints on that bucket (bailing can) and tell us who else was there that morning,” Clarence’s brother, William, added. “Then he says the bucket got lost. Somebody explain that.”

Eight decades later, the families of Joseph Nuccio and Nick McCrory still await that explanation.