Donna Bahm murder remains unsolved

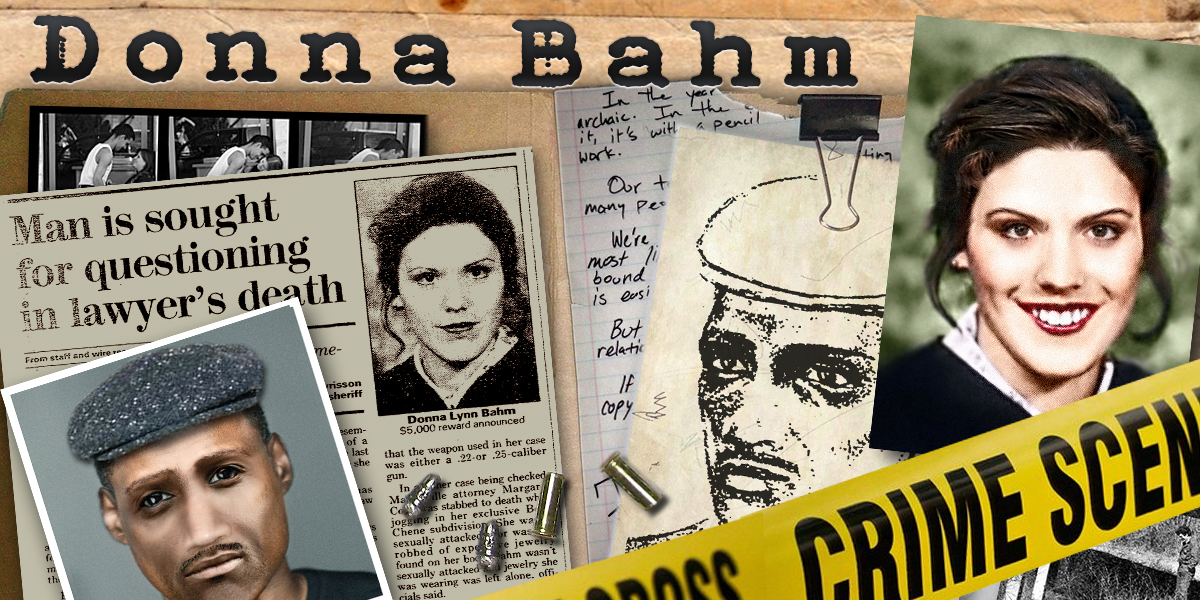

Thirty-three years ago, January 23, 1988, the St. Helena Parish Sheriff’s Office responded to a call on the Tickfaw River. Around 2:30 that Saturday afternoon, swimmers discovered the body of Donna Lynn Bahm. The 31-year-old Amite attorney had gone missing two days earlier. The swimmers found under a bridge on Louisiana Highway 1045 near Hillsdale.

According to St. Helena Coroner Dr. L.E. Stringer, after striking her twice in the head with a tire iron and fracturing her skull, her murderer popped a pair of.22 caliber slugs into her chest. Afterward, her assailant used a 30-foot logging chain to tie his victim to a 15-inch tire rim before tossing the rim over the guardrail like an anchor, submerging the body beneath the floodwater. Underneath the bridge, waves 3-feet higher than usual dropped two days later, exposing Donna’s partially clothed corpse.

The Tangipahoa Parish Sheriff’s office released a person seen leaving the courthouse with the attorney before she vanished, and seven months later, Sheriff Ed Layrisson announced the arrest of 38-year-old Alvin “Bubba” Daniels, saying his office charged Daniels, a private detective working for Donna Bahm, with two counts of extortion.

One month earlier, on July 28, 1988, Donna Bahm’s father, Edward Bahm, received letters from someone, who police later determined to be Daniels, claiming to have evidence that could prove who killed Donna.

Initially, Daniels requested $30,000 for the information, instructing Ed Bahm not to inform the sheriff’s office and to follow his orders. Otherwise, Daniels would not release the evidence.

After one failed attempt to deliver the money, Daniels contacted Bahm again, informing Bahm that he avoided the money drop because he knew someone had notified the sheriff’s office. This time, he demanded $50,000 for his information.

Detectives arrested Daniels during his second attempt to pick up the money. After his arrest, he told police he made the phone calls and sent the letters to Bahm soliciting cash but insisted he knew nothing about Donna’s murder.

He told police that, before becoming a private detective, he lived his life as a conman and an occasional thief, but he never killed anyone.

In February of 1975, a highwayman stopped a vehicle at an intersection in Amite and then forced his way inside the car. The robber locked the driver, a local insurance agent, in the trunk of the car and drove to a wooded area near Arcola, where he pulled the man from the vehicle, shot him in the eye, and then left him for dead.

Soon after, investigators matched a fingerprint on the car to Eddie Charles Griffin, 23, of Amite, and when the attending physician released the driver from Hood Memorial Hospital in Amite, detectives asked him to pick his assailant from a lineup of four men. The victim selected Eddie Charles Griffin, and the District Attorney charged Griffin with attempted murder, aggravated kidnapping, and armed robbery.

At Griffin’s trial, defense attorneys insisted their client had not committed these crimes, claiming that the defendant had left his fingerprint on the car window 24 hours earlier, when the driver, a homosexual, propositioned him for sex.

To support this claim, the Defense called a Fluker resident, Alvin “Bubba” Daniels, to the stand.

Judge Burrell Carter and a 12-member jury watched intently, while Daniels, dressed in his Sunday best, described, ever so eloquently, how he frequented the area over the last year and that the driver of the car often propositioned him for “homosexual activity.” Daniels described in detail how the driver regularly stalked pedestrians, stopping his car and offering unsuspecting males a ride in exchange for sex.

When the pedestrian walked over to the car, Daniels said, the driver would roll down his window halfway, causing the pedestrian to touch the glass as he listened to the driver’s pitch.

“If you look at that window close enough,” said Daniels, “you may find my prints on that glass, along with several other innocent men this sexual predator stopped last week.”

The jury appeared moved by the testimony, at least before the prosecution’s cross-examination.

“Mr. Daniels,” the prosecutor began, “Can you tell the jury where you slept last night?”

The Defense objected, but Judge Carter allowed the prosecutor to continue.

“And afterward,” the persecutor continued, “perhaps you can tell the court where you were last week when the car-jacking occurred?”

“Isn’t it a fact, Mr. Daniels,” he said, “that you have been sleeping upstairs in this very building, a prisoner of the Tangipahoa Parish Sheriff’s Office?”

Once again, the Defense objected, this time, specifically citing Section 495 of Title 15 of the Revised Statutes. No witness, defendant or not, can be asked on cross-examination whether he has ever been indicted or arrested, and can only be questioned as to a conviction. However, the prosecutor had not mentioned Daniels’ indictment and arrest for an armed robbery of his own.

Days before the robbery the 21st Judicial District Court accused Eddie Charles Griffin of committing, at 7:59 on the morning of February 3, 1975, Flo Bankston reported to the Tangipahoa Parish Sheriff’s Office that a bandit robbed her grocery store three miles east of the town of Arcola. The robber, she said, drew a snub-nosed revolver from a lunch pail and demanded all the cash, a little over $400, from her cash register. A week later, Flo Bankston selected Daniels from a line-up at the courthouse as the robber of her store.

The jury found Eddie Charles Griffin guilty, and Judge Carter sentenced him to 99 years with the Department of Corrections.

The following July, another jury convicted Alvin Daniels, and District Judge Leon Ford III committed him to 30 years in the Tangipahoa Parish Prison. He served 10 years before his release for good behavior.

Two years later, Daniels claimed to find information on Donna Bahm’s murder and tried to sell that information to Donna Bahm’s father. Readers can find minute details of the extortion scheme’s comical failings in my book, Bayou Justice: South Louisiana Cold Case Files.

As with his earlier con, Daniels won a 30-year conviction and served ten years. Outside, he claimed to be reborn. No more private detecting for him. God had called him to be a minister.

With a bit of misdirection, a conman convinced the world that police had caught and punished someone for the murder of Donna Bahm. However, that could not be farther from the truth. Donna’s murderer still walks free, and his name is not Bubba Daniels.