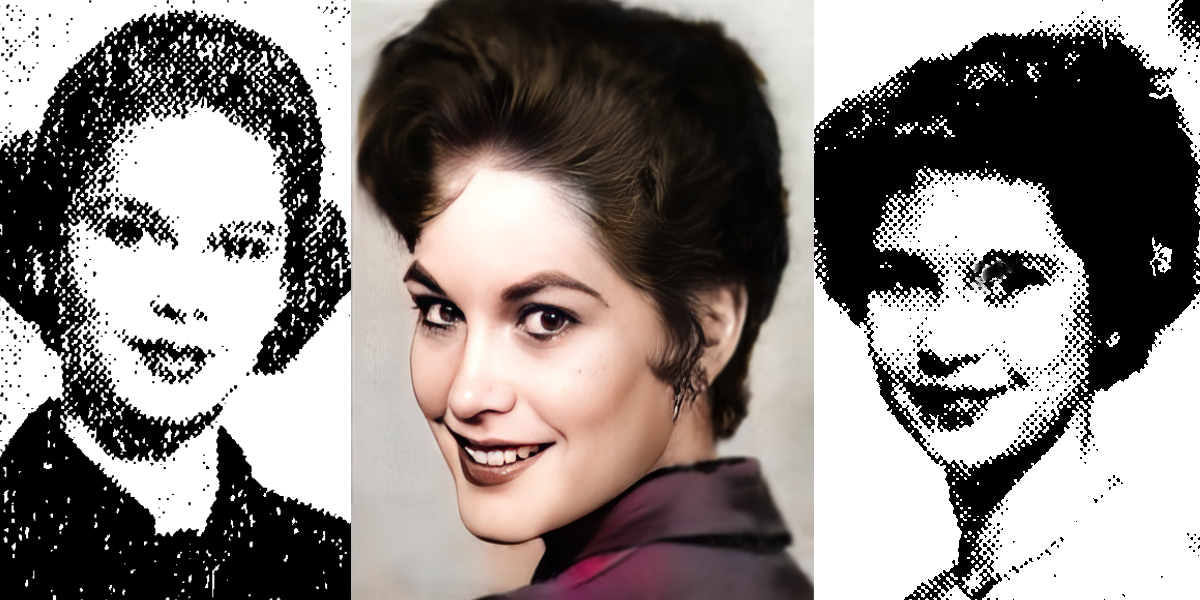

Jane Clement missing since 1963

Last week, the first cousin of a journalist and actress missing since 1963 phoned me about the case I recounted three years ago. The caller’s father became an amateur sleuth when his sister vanished. According to the missing girl’s cousin and uncle, investigators today may be close to locating Jane Clement.

Autumn 1959, closing night for the Southeastern Louisiana College stage play “Suspect,” and news reporters from three Hammond newspapers had questions – not for the play’s lead, Carol Cook of New Orleans – but for Freshman actress from Baton Rouge actress in a supporting role, 18-year-old Hannah Jane Rowell.

“Miss Rowell,” one reporter shouted, “Is it true that an agent from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer has contacted you?”

“When are you leaving for Hollywood, Miss Rowell?” another asked.

Three days earlier, a New Orleans Times-Picayune columnist leaked details of Jane’s springtime lunch in the French Quarter with Hollywood Director and Screenwriter Nunnally Hunter Johnson. According to the columnist, Johnson came to New Orleans for Mardi Gras, scouted area talent, and caught Jane’s performance in an earlier production at Southeastern.

“Do you have news to share, Miss Rowell?” the first reporter persisted.

“Okay,” Jane said, “I do have something to say.” The 5’4” beauty stood at the edge of the stage, twisting her dark brown hair as he spoke, wiping her eyes with a blue-laced handkerchief.

“I am leaving Southeastern after this semester,” she said.

“Are you crying, Miss Rowell?” the reporter asked.

“Tears of joy,” she answered. “But it’s nothing to do with Hollywood. I have abandoned this motion picture foolishness and accepted my sweetheart’s marriage proposal. He was a track star at the University of Houston in Texas, and today is a high school coach and teacher in Baton Rouge.”

“But what about tinsel town, Miss Rowell?” a reporter asked. “We read you were going to be the next Ava Gardner.”

“No,” Jane replied, “But I will soon be Mrs. Wilton Clement.”

As she predicted, the following year, she did marry. The marriage produced two children, an infant, and a toddler, left behind when Jane Rowell Clement vanished in 1963.

When she disappeared, Jane’s estranged husband told police she had abandoned her family for Hollywood. However, since her disappearance almost 50 years ago, Jane Rowell Clement has not appeared in any motion picture.

She has not appeared anywhere.

Jane’s mother, a Mississippi schoolteacher, gave birth to Jane in Jefferson County in 1941. Jane’s father worked days as a farmer and nights as a moonshiner.

Before Jane’s seventh birthday, the family moved to Baton Rouge, where her mother and father died before Jane’s twelfth birthday. Jane and her four orphaned siblings shuffled between aunts, uncles, teachers, and family friends throughout their childhood.

Despite this tragedy, Jane developed into a bright, personable teenager. During her last years at the hospital, her mother had kept a diary, which Jane saw as an inspiration. At Istrouma Junior High School, Jane took top honors. Reporting on school events for the Baton Rouge Advocate, she quickly became popular among her peers, who selected her homecoming queen.

In addition to writing, Jane loved drama and the stage. At Istrouma High School, she was the first person to win “Best Actress” for three consecutive years for her portrayals in annual school productions. She starred in “Blithe Spirit,” “Our Town,” and “You Can’t Take It with You.”

After she left Southeastern, Jane directed stageplays at Istrouma High School and worked again for the newspaper. Subscribing to correspondence courses and home studies, she worked to improve her craft and sold fiction to several pulp magazines.

On Christmas Eve, 1962, a fight with her husband over Jane’s writing became physical. The following day, Jane’s doctor admitted her to the Baton Rouge General Hospital for treatment of deep bruises on her neck and back.

The doctor discharged her on New Year’s Eve, but she never lived with Wilton Clement again. A Baton Rouge court granted her a legal separation on March 18, 1963, along with custody of the children and the residence on Sorrel Avenue.

Alone with her children, Jane began writing a novel, left unfinished when she disappeared. Curiously, Jane also authored a lengthy letter to be given to her infant daughter when she came of age.

Jane told her brother that she feared living alone. Her brother, Wylie Rowell, visited her and the children often, sometimes spending the weekend. Still, as a precaution, Jane asked a friend, Mrs. Dudley Jeffers, to telephone her daily and to notify Wylie if the day came when she did not answer.

Saturday morning, April 6, 1963, Wylie drove up from New Orleans and spent the night at Jane’s. Sunday morning, Wilton Clement picked up the children for his scheduled visitation. But, according to Wylie, Clement and Jane argued before he left.

After lunch that Sunday, April 7, 1963, Wylie, his friend Gerald Sanders, and Jane took a boat across the river. Later, Wylie departed for New Orleans, unaware that he would never see his sister again.

Ten days later, Mrs. Jeffers called Wylie long-distance. Jane hadn’t answered her telephone for several days. At first, Mrs. Jeffers assumed Jane had left for New Orleans with Wylie, but, she said, she grew worried and decided to call Wylie to confirm.

Wylie left work, driving frantically to Baton Rouge, and met Mrs. Jeffers at Jane’s house, facing two locked doors.

Wylie broke the glass in the back door, unlocked it, and entered the kitchen. He found a hamper of mildewed clothing and half a pack of cigarettes on the clothes dryer. Everything else in the house appeared as it had two weeks earlier.

Jane’s makeup and clothing appeared in place, excluding the outfit she had worn that Sunday. The only thing missing from the house was a pink bedspread. Wylie remembered it because he had slept on the couch and used it for cover.

Both the Baton Rouge City police and the sheriff’s office responded to Mrs. Jeffers’ call. But, before the search concluded, the district attorney presented evidence to a grand jury that, even today, has never been made public.

Investigators questioned Wilton Clement within an hour of Jeffers’ call. Clement said he last saw Jane on Monday, April 8. He had returned the children the night before, but, he said, Jane called him that morning to come back and get them. He said she had a job offer, working for a wealthy club owner on Bourbon Street, and she needed to meet the man for lunch.

Clement said he had tried to call Jane later but got no answer. So he assumed she had taken the job and stayed at her brother’s in New Orleans.

Neighbors reported nothing unusual. Police dispatched bulletins regarding her disappearance across the country and contacted Jane’s friends and casual acquaintances in Mississippi, North Carolina, Florida, Pennsylvania, and Alabama.

None spoke to her after April 7, 1963.

For months, Jane’s aunt, Mrs. Mary G. Baker in Natchez, Mississippi, ran a newspaper advertisement in the Advocate offering a $300 reward for information concerning her niece’s disappearance without response.

In December 1963, police found a woman’s body near the Benbrook Lake Dam outside Fort Worth, Texas. Jane’s physical characteristics matched those of the estimated six-month-old corpse, but Jane’s dental records did not.

In 1965, columnist Jim Crain met with Wylie Rowell to discuss Wylie’s sister and her strange disappearance.

“It’s the sort of thing you never get over,” Wylie said. “There has been no peace for our family since it happened. It is worse than someone you love dying,” he said. “It’s a nightmare, never knowing what happened or how and why it happened.”

Crain reported that Wylie gazed into a cup of black coffee at Café Du Monde for a few moments before he could continue. And then he said, “I know one thing for sure. My sister loved her children too much to run away.”

“What do you think happened to her?” Jim Crain asked.

“Murder,” Wylie Rowell replied. “I’d stake my life on it.”

Wylie G. Rowell died in 2008 at age 72.

“I met my uncle at a café when I was in college,” Jane’s daughter, Janet, told me in April 2020. “He gave me some photos. It was obvious that he had never gotten over my mother’s disappearance. They must have been close.”

Janet said that Wylie “appeared to be on drugs of some sort” that day. Years later, her uncle apologized. He said he had been so nervous meeting her for the first time that he left his box of family photos. Later that week, he returned to the café, but the box had disappeared.

“My mother’s family was a little crazy,” Janet said. “Her father shot himself, Wylie had a drug problem, and Patsy, my mom’s older sister, ran away years before my mother disappeared.

Janet said her mother named her after the last woman to help raise the Rowell children, a Baton Rouge schoolteacher named Janet Robinson. Robinson told Janet that she saw Jane years after her disappearance at a gathering of people in Pascagoula, Mississippi. However, the woman resembling Jane disappeared in the crowd before Robinson could reach her. Questioning the couple the woman had been sitting with, both confirmed the woman’s name was Jane.

“Wylie, and maybe the police, think my dad did something to her, but you will never find a more easy-going, mild-tempered man,” Janet said. “I didn’t know my mother, but I know my father. She may have been murdered, but he wasn’t responsible.”

More next week.