Hunter Horgan’s tragic murder revisited

The Reverend Hunter H. Horgan, III, an Episcopalian priest and a native of Hammond, was found stabbed to death in his church office in 1992. Nearly two decades passed before anyone served time for the heinous crime, and today, many feel true justice went unserved.

The Right Reverend R. Heber Gooden, assistant bishop of the Louisiana Diocese, ordained Hunter Horgan, on a Wednesday, April 25, 1973, at 6 p.m. following a sermon from Reverend Urban T. Holmes, the dean of St. Luke’s Seminary in Sewanee, Tennessee. At the time, Hunter was the deacon-curate at Trinity Church.

He was born in Meridian, Mississippi, but Hunter grew up in Hammond. He attended McNeese State College and graduated from Louisiana State University, earning a master’s degree in education.

“Hunter is just well-liked, well-known — the kind of guy everybody remembers,” said Phil Ward, a camp counselor with Hunter in the mid-1960s and a classmate of his at the seminary. “…We were all surprised he became a priest, but then we weren’t.”

After completing his seminary work at Virginia Theological Seminary in Alexandria, he worked as an aide to United States Senator William Proxmire of Wisconsin from 1970 to 1972, leading the senator’s Inter-seminary Church and Society Program in Washington, D.C.

Throughout the 70s and 80s, Senator Proxmire made national news with his Golden Fleece Awards, singling out parties responsible for government waste, questionable scientific research, and outlandish public works projects. His first award, for example, went to Elaine Hatfield and Ellen Berscheid when the National Science Foundation (NSF) granted them $84,000 to validate the existence of love in America.

As Proxmire’s awards program launched, Hunter Horgan returned to Louisiana, accepting a chaplain position and faculty member position at Trinity Episcopal School.

Hunter served as assistant rector of Trinity Episcopal Church in New Orleans and chaplain of Trinity Episcopal School from 1972-79. He was also the youth advisor for the New Orleans Convocation of Episcopal Churches during this period.

He served as rector of St Paul’s Episcopal Church in New Orleans from 1979 through 1989, when he arrived at St. John’s Episcopal as a supply pastor. Soon after, he became the church’s full-time minister.

Thursday morning, August 13, 1992, Thibodaux Police Chief Norman “Nookie” Diaz told reporters that a parishioner found Reverend Hunter Horgan, then 47, beaten to death in the St. John Episcopal Church Hall. Diaz said Hunter had been stabbed and hit on the head several times. He also told reporters there had been no forced entry into the building.

“We feel the victim – the pastor – let the person in,” Diaz said.

Diaz said the church congregation had raised a $12,000 reward for information on the priest’s killer. Still, surprisingly, this resulted in no solid leads.

Chief Diaz said police found Hunter’s gray 1990 Toyota Camry in the 1200 block of St. Charles Street, a half-mile from the church, parked with the license plate facing a fence. Inside the vehicle, the State Police Crime Laboratory found nothing out of the ordinary, Diaz said.

Diaz said that Hunter, who also served as church rector and as vicar of Christ Episcopal Church in Napoleonville, was last seen alive in the church hall at St. John’s between 5 and 6 p.m. on the day before the church office manager discovered the body.

That morning, August 13, 1992, parishioner Ron Graham entered the church hall. He found Hunter’s fully clothed body lying face down on the floor with blood stretching from the hallway to the kitchen. It appeared, Graham told reporters, that his friend had been attacked and killed in his office the previous evening.

“I feel most probably it was somebody he was counseling,” Graham said. “Maybe they revealed something to him that they didn’t want to be known and ended him.”

Three days later, the Thibodaux Police Department asked other law-enforcement agencies for assistance, including the Louisiana State Police, the state Attorney General’s Office, and the Terrebonne Parish Sheriff’s Office. Still, for decades, police made no arrests in the case.

According to the coroner’s report, the murder of Hunter Horgan was shockingly brutal. He sustained multiple blunt-force injuries to the back of his head, resulting in four to five deep lacerations. At least one of the cuts from an unidentified blunt object was so fierce that it caused a depressed skull fracture that pressed bone inward into the brain tissue.

His attacker violently subjected Hunter to multiple blunt-force injuries to the right side of his face and neck. One injury at the base of his neck transected his carotid artery through and through. Either this injury or the head trauma alone would have been sufficient to cause his death. Additionally, numerous wounds consistent with defensive wounds on Hunter’s arm, wrist, and hand indicated that he was conscious and struggled vainly for his life during the vicious attack. When the parishioner discovered Hunter’s body, one of his trouser pockets was askew, the inside lining sticking out, and his wallet missing.

While collecting fingerprints from various locations in the church hall, investigators found a bloody print on a small table near Hunter’s body and another on a water faucet in the church hall kitchen near some drops of diluted blood. These investigative efforts, which included conducting over two hundred interviews and fingerprinting all church members, according to police, yielded no suspects for several years.

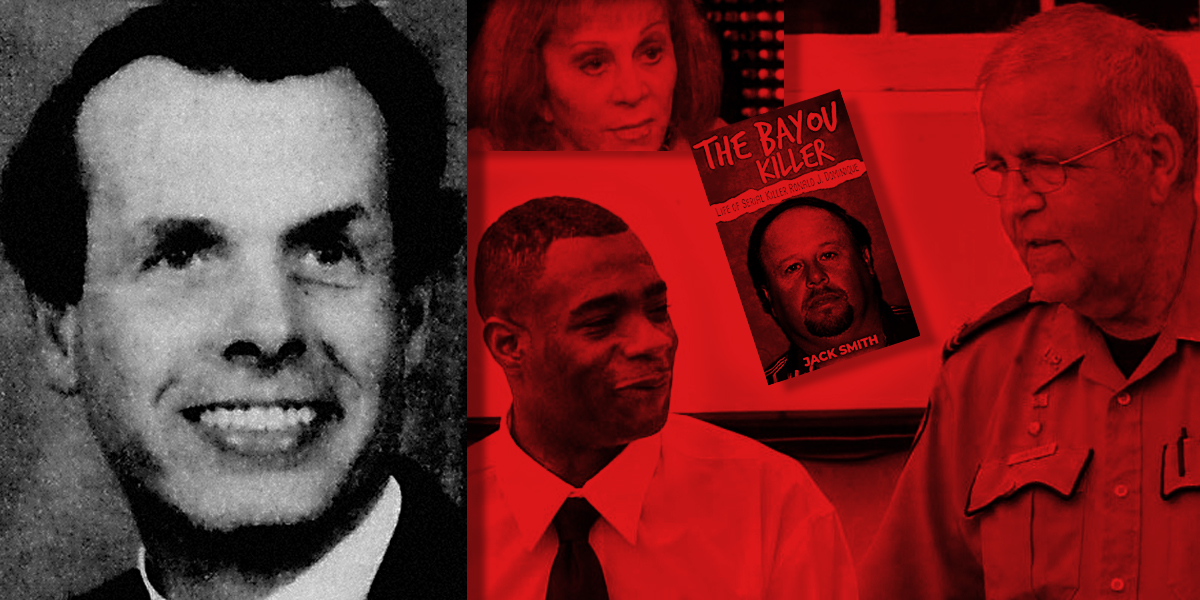

In 2007, Porter Horgan told reporters he doubted the police would resolve his brother’s murder. Thibodaux Police, Porter said, wasted time trying to pin the murder on serial killers, including alleged south Louisiana mass murderer Ronald Joseph Dominique, who police charged in 2006.

Dominique worked in a flower shop across the street from Hunter’s church in the early 1990s and may have known him. Police attempted to get Dominique to confess to the crime. However, he declined, reminding them he raped and asphyxiated all of his victims, but he never beat anyone to death.

The Thibodaux Police Department’s use of psychic Sylvia Browne, best known for her appearances on television talk shows, also upset Porter Horgan. The City of Thibodaux paid the California-based cognitive $400 for a 30-minute “reading” in which she claimed that “somebody with the street name of King directed gang people to do it.” When asked for a name, Browne declined, saying she was “concerned about the ethics of doing so.”

Browne also told police, “The priest was killed by a young mulatto homosexual who was enraged by Hunter’s rejection of his advances.” She said, “Someone was in love with the priest, and he [Hunter] wasn’t predisposed to be in love with a man.” She said, “The priest was trying to help him.”

Browne’s imaginings likely grew from a stereotypical assumption that Episcopal priests had to be celibate or gay. Hunter Horgan was neither.

Hunter and his wife, Marda, had a son, daughter, and three step-children. The pastor lived in an apartment in Thibodaux, while his wife lived in Metairie. The couple planned for her to move to Thibodaux after their youngest child finished high school. Marda never got that opportunity.

“The Thibodaux Police Department is lost,” the minister’s brother told a reporter in 2007. “I don’t think they could track an elephant in fresh snow.”

Porter Horgan said Thibodaux Police, mesmerized by the media attention the case received, missed the opportunity to arrest the guilty in the 90s when they failed to interview the proper individuals and evaluate the right evidence. “For some reason,” he said, “several important individuals were never interviewed.”

In May of 1998, Thibodaux Police received information that resulted in Derrick Odomes becoming a suspect. Odomes, at the time of the murder, was a juvenile, 14 years old, living approximately one block from the church.

Investigators advised him that he was a suspect in the murder and interviewed him regarding his involvement. However, Odomes denied knowledge of the killing, saying he had never been inside the church and had never met Hunter Horgan.

Following the interview, city police submitted Odomes’ fingerprint cards to the Louisiana State Police Crime Laboratory (LSPCL) for comparison with those at the crime scene. However, the lab found no matches.

In 2007, pressured by a local newspaper, investigators resubmitted the fingerprints to the crime lab. This time, technicians matched Derrick Odomes’s left thumbprint to a latent fingerprint lifted from the church hall water faucet in 1992. The lab requested that the police take additional “major case prints” from Odomes for further comparison, saying the original prints lacked sufficient ridge detail in some areas.

Officers collected full case fingerprints utilizing a new “ink and tape technique” said to provide greater ridge detail. Using fresh prints, LSPCL analysts identified another match to the bloody fingerprint found on the tabletop next to Hunter’s body.

On September 26, 2007, investigators indicted Derrick Odomes for Hunter’s murder. At trial, the prosecution presented testimony that Odomes made threats sometime in the 1990s against a jail employee he had told about the crime.

Derrick Odomes received the maximum juvenile sentence under 1992 state guidelines in 2011. However, the seven-year sentence he received paled compared to the life sentence he already served. That sentence, issued under the state’s habitual offender law, resulted from the string of unrelated felony convictions Odomes earned after Hunter Horgan’s murder.

Today, Odomes resides at a Louisiana Department of Corrections minimum-security facility in Baton Rouge.