Hammond dentist tarred and feathered

“You can’t rightly call it tarring, Your Honor. We used a cold creosote and tar mixture, stuff we use on corn to keep the crows off. It ain’t hot, so it doesn’t burn the skin. Well, not if it’s cleaned off before the sun comes up.”

“Mr. Starns, call it what you will,” said Judge Nat Tycer. “The fact remains. It is illegal to strip a man naked, stick feathers to his body, and drop him on a crowded street.”

“But Nat, I brought him home. It’s not my fault he lives above the dentist’s office, and I didn’t put his office across the street from the Tropic Café.”

“And I suppose you were unaware that the restaurant was open all night?”

“I wanted to drop him at the hotel and make him walk to his place, but my brother Newton said that would be cruel because he might not make it home before sun up.”

“Where were your brothers in all this?”

“Oh, they didn’t do any feathers. No, sir, they just watched. My brother, Henry, came up with the idea though. Me, I just wanted to shoot the bastard.”

Before I started this column, when someone said “Bayou Justice,” I usually thought of this story. My great-grandfather, W. O. “Paw Bill” Courtney, retold it routinely when I was a kid. My grandmother, “Maw Telliua,” insisted he had embellished some of it. I never cared. I loved the story regardless.

Imagine my surprise decades later, finding these headlines from 1930: “Hammond dentist tarred and feathered,” “Starns admits tarring, labels dentist homewrecker,” “Tar and feather witnesses under guard,” “Crowds fill tar and feather courtroom,” “Tar and feather mistrial!”, and “U. S. court refuses to hear tar and feather appeal.”

These headlines screamed across the front pages of New Orleans and Baton Rouge papers. They made their way into newspapers across the country. The story was big news for quieter times, but like most true crime stories, this one ends in sadness and gunfire.

The trouble started on Sunday, May 25, 1930.

Isaac G. “Ike” Starns returned home from a Mississippi Shriner’s convention to neighbors whispering that his wife had spent a few nights with Dr. Sedgie L. Newsom, the family dentist. The following Monday evening, Dr. Newsom answered a house call at the Tangipahoa-Livingston parish line, only to be run off the road by Starns’ canary-yellow, wire-rimmed Ford Chrysler.

A .38 revolver in his hand, Starns ordered Newsom into the car and drove him into the woods near Albany. There, Newsom stood facing a roaring fire, surrounded by five men. Ike Starns held a pillow in his hand.

Starns would later tell a packed courtroom, “I told him the pillow came from my wife’s bed and ordered him to smell it before we stripped off his clothes. I said, ‘You want to be naked against my wife’s pillow; I’m going to grant your wish.’ I painted him up with the creosote. Then I ripped the pillow apart and stuck the feathers to him. Duck feathers, too. Really expensive.”

On May 27, 1930, Hammond Police Chief W. H. Rimmer said the case was under investigation. Dr. Newsom, then staying with relatives in Mississippi, had not suffered any physical injury after a physician assisted him in removing the feathers.

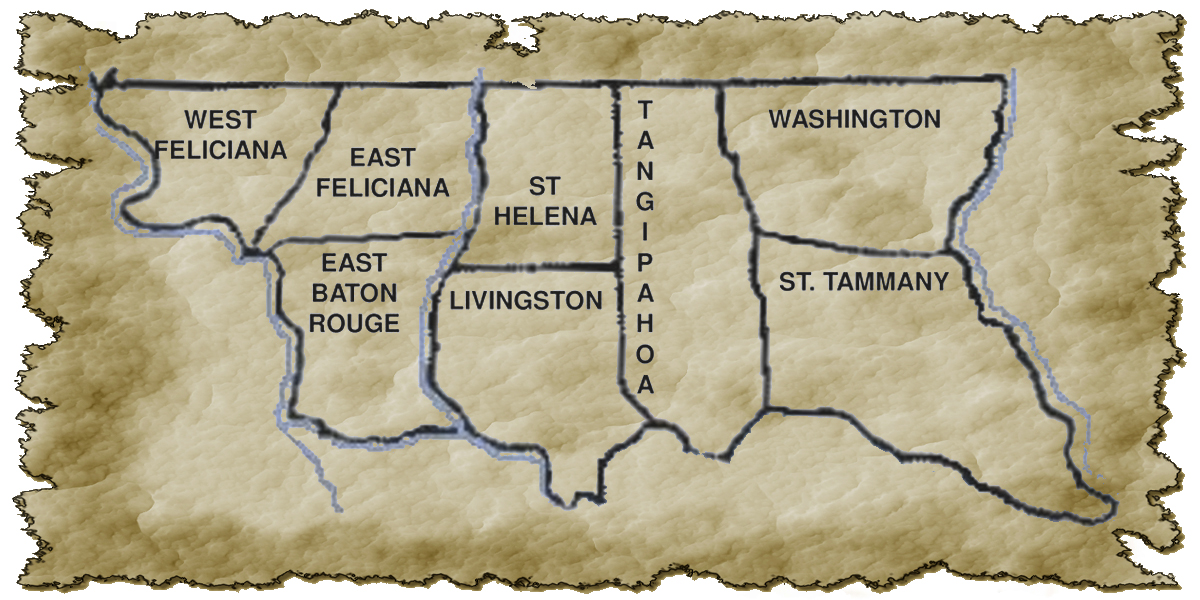

Tangipahoa Parish Sheriff Frank M. Edwards told the States-Item that he was “working with the sheriff in Livingston Parish and expressed his determination to arrest members of the Tar and Feather Mob within 24 hours.”

The next day, deputies in two parishes arrested the five Starns brothers, all prominent and wealthy citizens well known in Hammond. Berlin Starns owned the largest furniture store in South Louisiana. Ike Starns, 42, had a lumberyard and general store in Livingston. His brother, Newton, 39, owned two stores, one in Frost and another in Springville. Charles, 36, owned a flour distribution business in Baton Rouge. Henry, 25, owned a store in Holden, and Gordon, 22, worked at his father’s in Hammond.

Following the arrest and news coverage, Representative Marcus Rownd of Livingston spoke from the house floor, chastising a New Orleans newspaper that described the Starns brothers as “outlaws from the free state of Livingston.”

“This article said that nightrider activities are still carried out with the same frequency as in earlier days. This is untrue. Livingston Parish is one of the most peaceful in the state. We have schools. We have churches and lodges of various kinds, and any man, woman, or child would be safe in this parish—at least as far as the citizens of the parish are concerned.”

“I want it on the record. My people are not outlaws,” he said. “The people of Livingston Parish are honest and law-abiding. The staff of these newspapers should visit and get acquainted with people before they slander them. I take this as a personal insult to my people and demand that this newspaper apologize.”

When the trials began, the case made national news.

The 21st Judicial Court tried the Starn brothers living in Livingston Parish in Springville, and those in Tangipahoa stood trial in Amite. Amite Defense Attorney Amos L. Ponder represented all five, arguing that Louisiana’s “unwritten law” was their best defense each time.

“I found it difficult to advise my clients against doing what I—or any judge or juror here today—would have done if their family were under attack. When the day comes that morality and marriage do not come first, this country will go to hell flying.”

Ponder said that the breaking up of the Starns home by the misconduct of Dr. Newsom and Gladys Starns was a mental punishment to Ike and that the brothers chose the retaliation to inflict a similar mental punishment.

“My clients wanted the punishment to fit the crime, Your Honor.”

The lawyer said he had no objection to a man womanizing provided he “confined himself to targets that did not attack girlhood or the sanctity of the home.”

Ike Starns also testified. “Yes, I did tar and feather Dr. S. L. Newsom. I put the tar and feathers on him with my own hand. I decided this was better than most men would have done to someone who breaks up happy homes. He should be thankful I spared his life.”

After three criminal trials, a jury acquitted Ike and his brothers.

Dr. Newsom filed suit in civil court afterward, and a judge awarded him $6,000.

As this story ends, I have vindicated my grandfather. Paw Bill’s tale of the tarred and feathered dentist proved more fact than fabrication. Compared to the newspapers of the day, Paw undersold his story. He left out the saddest parts.

Ike Starns was a war hero, serving the 348th Infantry in France during the First World War. After the war, he joined law enforcement in tracking down two of the six bank robbers hanged for the Independence murder of Dallas Calmes in 1924.

Starns never reconciled with Gladys, and he never forgave Newsom.

In 1934, an intoxicated Starns climbed out of his canary-yellow Chrysler in front of the Central Drugstore downtown and fired two .38 caliber rounds into Newsom’s office window. The dentist stood in the stairwell of his building, frozen, holding his unfired pistol.

Hearing the shots, police officers crossed the street from the Columbia Theater, and Starns turned his gun on them. They returned fire, and Starns fell dead on Thomas Street, where the feathered Dr. Newsom had stood four years earlier in front of his locked office without keys or pockets to carry them in.

Today, we would call Starns’ death suicide by police, but in 1934, most just said Ike Starns died from a broken heart.