Bayou Justice:

Louisiana's

Cold Case

True Crime Podcast

The swamps of Louisiana have stories that demand to be told. Cold cases that refuse to stay closed. Murders that shaped communities and questions that still linger decades later. Bayou Justice examines these cases with the rigor of a veteran investigative journalist—drawing on evidence, court records, and interviews with those who lived through them. This isn't entertainment. It's investigation. Read HL Arledge's Bayou Justice book series—or subscribe to the podcast.

950+

Subscribers

1.8K

Facebook Followers

10+

Episodes

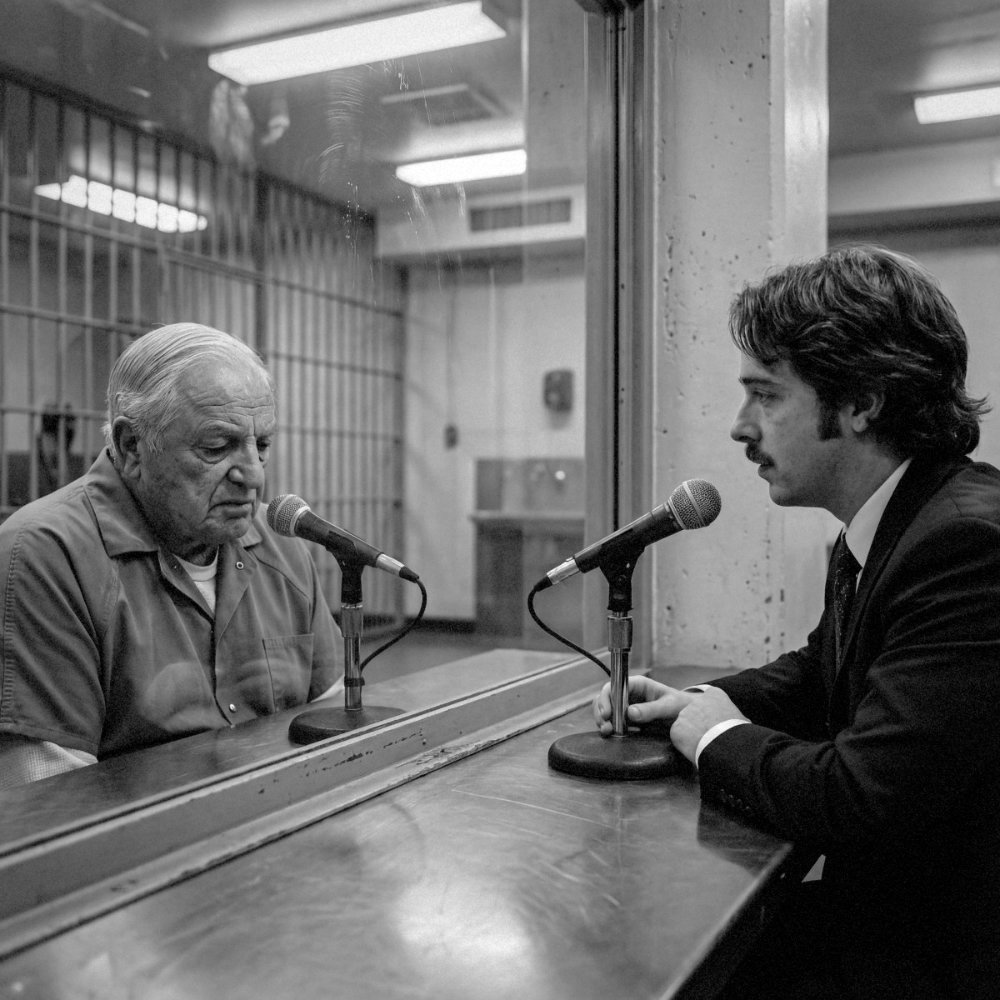

About your host

HL Arledge speaks for

the dead to a mature

True Crime audience

Over thirty years thawing cold cases. Nearly five decades in the field. Gather the thoughts of a legendary investigative journalist as he turns his lens on South Louisiana's most compelling crimes—from forgotten cases gathering dust in parish archives to unsolved crimes still making headline. No sensationalism here. Just forensic storytelling from someone who's interviewed the witnesses and the detectives. He's reviewed the evidence, and knows which details matter.

Subscribe now for the narratives that define a region's darkest chapters.

10th

Experience

HL Arledge's journalism career expands four decades.

40 years as an Investigative Reporter

Get to know the voices of the dead as our host brings passion, expertise, and a deep love for justice to every episode.

Each one shares his unique perspective and dedication to delivering content that resonates with true crime lovers everywhere.

1981

Newspaper interview in New Orleans

1987

Radio interview regarding JFK assassination

2023

Transitioning from Radio and Newspapers

Popular Episodes

Whether you're encountering these cases for the first time or following a decades-old mystery, our collection offers the depth and rigor that serious true crime demands. Join us.

00:04:34

Dec 12, 2025

Introducing: The 2026 Bayou Justice theme

01:03:07

Aug 6, 2023

5 Louisiana Cold Case Crimes selected by you

00:21:18

Mar 25, 2020

Frankie Richard is Dead, Book cancelled

00:38:49

Oct 8, 2023

Where is Barbara Blount?

00:44:12

Sep 11, 2023

Who killed Kimberly Womack?

00:52:25

Aug 27, 2023

Who Killed Nanette Krentel and her pets?

00:14:24

Aug 9, 2023

Who Killed the Store Clerk Jerry Monus?

00:10:26

Jun 26, 2022

Why can't police stop New Orleans snipers?

00:11:52

Mar 25, 2020

The Hi-Ho Mafia Murder

Subscribe for tips on upcoming episodes

Stay up-to-date with all our latest episodes, exclusive interviews, and deep dives into the world of music. Subscribe now and get notified whenever new content drops—right at your fingertips!

Bayou Justice explores South Louisiana's most compelling unsolved murders and mysteries through meticulous investigation and firsthand accounts. Hosted by a veteran investigative journalist with four decades in the field, each episode examines cold cases and historically significant crimes—drawing on interviews with detectives, legal experts, victims' families, and those closest to the investigations. By amplifying these cases, Bayou Justice supports ongoing efforts to bring closure to families and justice to victims. Listen and subscribe to the podcast. Read the book series. Join the investigation.

Pages

DISCLAIMER: All persons are presumed innocent until proven guilty.

For the Bayou Justice book series, newspaper columns, and podcast episodes. All rights reserved © 2026 by HL Arledge.

All content on this site is copyrighted by the author and may not be republished elsewhere without the explicit permission of HL Arledge.